It is Saturday 19th December 1981. The weather in Cornwall on the south coast of England is horrific – winds are gusting at up to 100mph (hurricane force 12 on the Beaufort scale) and waves are up to 60 feet (18 meters) high.

A coaster called the MV Union Star is travelling from Ijmuiden in the Netherlands to Arlow in Ireland, on its maiden voyage, with a cargo of fertiliser. It had a crew of five, plus three members of the Captain’s family on board.

Eight miles off the coast of Cornwall the new ship’s engines failed and they were unable to be restarted. In such horrendous conditions, the powerless ship was blown towards rocks known as Boscawen cove, near Lamorna, 4 miles south of Penzance.

The MV Union Star issued a mayday call to Falmouth Coastguard who requested the assistance of a Royal Navy Sea King Helicopter from a nearby airbase flown by a United States Navy exchange-pilot, Lieutenant Commander Russell Smith. However, due to the extreme wave conditions, Lt Cdr Smith was unable to winch anyone off the ship.

The bad weather meant that the Coastguard in Falmouth had difficulty in contacting the nearest RNLI (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) station at Penlee but they were eventually able to contact the Coxswain Trevelyan Richards. He summoned the lifeboat’s volunteers and hand-picked a crew of seven to accompany him to the rescue of the Union Star. At 20:12, the Penlee RNLB Solomon Brown lifeboat launched to the aid of the stricken boat.

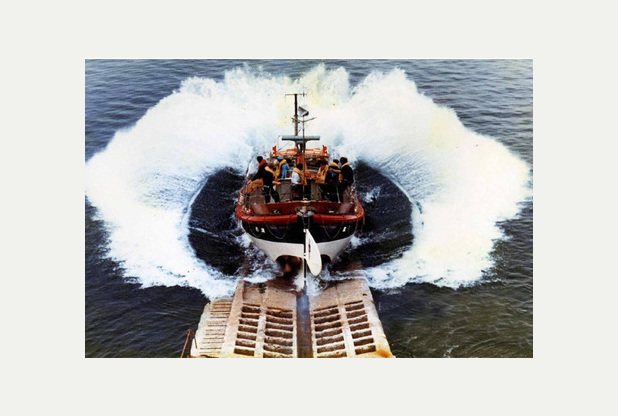

RNLB Solomon Browne launching from Penlee earlier in 1981

RNLB Solomon Browne launching from Penlee earlier in 1981

On reaching the vessel, the lifeboat made several attempts to draw alongside and eventually 4 crew members were able to jump onto the lifeboat. Shortly after this, Falmouth Coastguard lost radio contact with the Solomon Browne and were unable to re-establish communications.

The pilot of the Sea King helicopter reported afterwards that the rescue was “The greatest act of courage that I have ever seen, and am ever likely to see … They were truly the bravest eight men I’ve ever seen who were also totally dedicated to upholding the highest standards of the RNLI.”

After the loss of the Solomon Browne, lifeboats from neighbouring stations were launched to look for their colleagues from Penlee – one of the lifeboats from Sennen Cove was unable to make headway round Land’s End and the Lizard lifeboat found a large hole in it’s hull when it eventually returned to station. The wreckage of both boats was eventually found, however not all of the 16 bodies were recovered.

During an inquiry into the disaster the chairman stated that the loss of the Solomon Browne was due to “the persistent and heroic endeavours by the coxswain and his crew to save the lives of all from the Union Star. Such heroism enhances the highest traditions of the Royal National LifeboatInstitution in whose service they gave their lives.”

Coxswain Trevelyan Richards was posthumously awarded the RNLI’s Gold Medal, while the remainder of the crew were all posthumously awarded Bronze Medals.

2 days after the disaster, while the small community of Mousehole was still mourning the loss of 8 brave volunteers, a completely new crew had volunteered – they included 17-year-old Neil Brockman, whose father had died on the Solomon Brown.

The RNLI currently operate 236 lifeboat stations across the UK and are entirely made up of volunteers (except for the mechanics of the boats) and they are prepared to answer a call for assistance, in any weather, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. I read an article last year about the Coxswain of the Exmouth lifeboat who was retiring and who was finally be able to enjoy a Christmas Dinner without the possibility of his pager going off – the first time he enjoyed such a luxury since 1978.

There are tens of thousands of RNLI volunteers who contribute their time, energy and skills and who risk their lives every time they leave a harbour – these are the real men and women who we can call “heroes” of our generation. Indeed the word hero is always heard these days – one hears the term applied to people where it is not really necessary. A true hero is really never a hero at all; at least not in their own mind. The next time you are passing an RNLI station, please consider supporting them – you never know when you might be glad of their help

Leave a Reply